Reef Tank Basics

STABILITY OVER SPECTACLE: A SCIENTIFIC LOOK AT ALKALINITY, PH, AND CORAL HEALTH

In reef aquaria, the stability of alkalinity and pH is far more critical for coral health than the exact hour at which alkalinity is dosed. Whether alkalinity is added all at once in a single dose before lights-on or spread out throughout the day is far less critical than keeping the overall carbonate system stable and avoiding sharp swings.

In recent years, various dosing “styles” have appeared that place special emphasis on timing—for example, delivering the entire daily alkalinity requirement in a single shot near the start of the photoperiod and combining this with a short, intense light burst. These approaches are often presented as if the timing itself unlocks unique biological benefits such as “supercharged” photosynthesis or dramatically improved stability. From the standpoint of seawater chemistry and coral physiology, this is a problematic framing. The fundamental chemistry in a reef tank does not change because a dosing schedule has been given a name; what changes is the size and speed of the daily swings experienced by the corals.

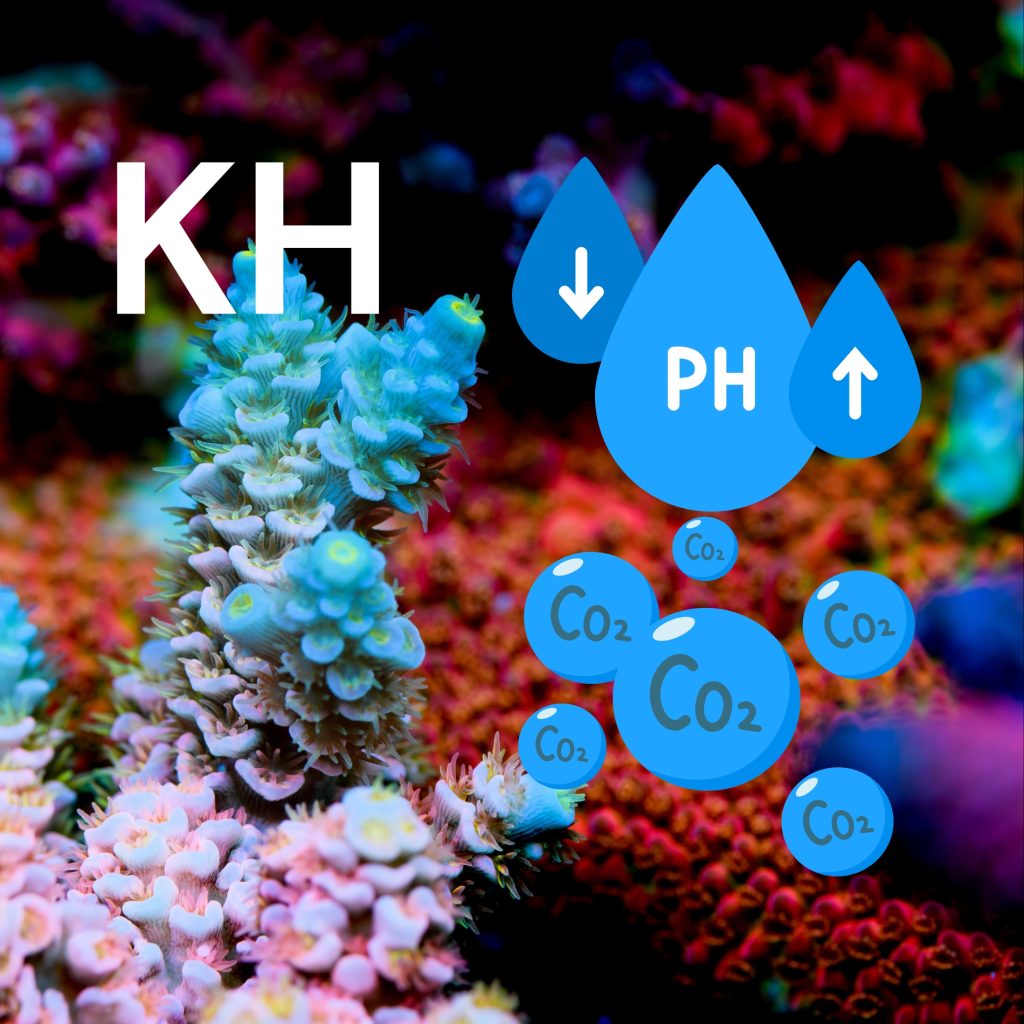

The key day–night changes in pH are driven primarily by CO₂ dynamics in the water, not by the timing of carbonate additions. At night, photosynthesis ceases while respiration by fish, corals, and microorganisms continues. This ongoing respiration produces CO₂, which dissolves in water, forming carbonic acid and releasing H⁺ ions. The result is a drop in pH. This is fundamentally a gas exchange and CO₂ balance problem, not an alkalinity dosing schedule problem.

A single large alkalinity dose can indeed cause a temporary pH rise, because the added carbonate and bicarbonate species can consume some free H⁺. However, this effect is transient and does not remove CO₂ from the system. As respiration continues and CO₂ remains elevated, pH will still trend downward along the same basic trajectory. In contrast, improving aeration, ensuring good access to fresh air, or using a refugium with reverse lighting physically alters the CO₂ balance and thus reshapes the entire pH curve, day and night.

Because of this, the scientifically sound ways to improve nighttime pH all focus on managing CO₂ and gas exchange, rather than on manipulating the clock. Practical methods include increasing aeration, ensuring vigorous surface agitation, and using an efficient protein skimmer that draws in adequate fresh air. Providing access to outside air for the skimmer or improving room ventilation can significantly reduce excess CO₂. Employing a reverse-lit refugium, where macroalgae photosynthesise at night while the main display is dark, can help consume CO₂ and blunt nighttime pH drops.

In appropriate systems, tools such as light kalkwasser use and CO₂ scrubbers on the skimmer intake can also help raise and stabilise pH by either consuming CO₂ (kalkwasser) or removing it from incoming air (scrubbers). These approaches address the underlying gas balance. Simply changing the time of alkalinity dosing cannot meaningfully “fix” a CO₂‑driven pH issue; it can only slightly reshape the daily pH curve for a few hours without touching the root cause.

Coral calcification depends on a stable carbonate system (alkalinity), adequate calcium, and a reasonably high, steady pH with as few fluctuations as possible. Both field observations on natural reefs and experimental data from aquaria show that sudden changes in alkalinity—such as rapid jumps of around 1 dKH or more—can stress sensitive corals, especially small polyp stony (SPS) species. These abrupt shifts are often associated with polyp retraction, tissue damage or loss, colour changes, and reduced skeletal growth. In practice, many experienced reefkeepers go to great lengths to avoid single, significant daily dosing events precisely because SPS corals in particular have been observed to respond poorly to such jumps.

Any dosing strategy that deliberately produces a pronounced daily spike or dip in dKH or pH, even if it conveniently coincides with the light cycle, is inherently less safe than one that keeps these parameters as flat and predictable as possible over 24 hours. Calling a deliberate daily alkalinity spike a form of “stability” is a misuse of the term. Proper stability means minimising the size and rate of daily swings, not reorganising them into a single, more dramatic peak.

It is also essential to recognise that pH and alkalinity, while related, are not interchangeable levers. One cannot safely “chase pH” by forcing alkalinity higher and higher, nor can a CO₂ problem be solved by compressing the entire daily alkalinity dose into a narrow time window. High alkalinity combined with significant, rapid variations often leads to burnt tips, a higher risk of precipitation, and an overall more fragile system. The goal is not to achieve impressive numbers or curves at a particular time of day; the goal is to maintain a stable, biologically comfortable environment around the clock.

From a chemistry perspective, a scheme that only specifies when to add the daily alkalinity dose is not a new or distinct reefkeeping system. It is simply a dosing schedule applied on top of the same, well‑understood carbonate chemistry that governs every marine aquarium. The underlying reactions—how bicarbonate, carbonate, CO₂, and calcium interact, and how they contribute to carbonate hardness and pH—do not change with the clock or with a name. What matters for coral health is that alkalinity and pH remain within an appropriate range and that any changes occur slowly and gently.

Modern dosing technology enables more refined matching of supplementation to actual consumption. Systems based on proportional consumption, such as the Modern Reef approach, aim to deliver balanced components in proportion to what corals and other calcifying organisms actually use and to distribute this dosing in small, frequent increments. By aligning dosing with actual consumption rather than an arbitrary time slot, these systems help keep alkalinity and pH within target ranges and highly stable throughout the full 24‑hour cycle. As a result, the entire carbonate system becomes more predictable and less prone to the stresses associated with rapid shifts.

None of this is an argument against balanced multi‑component supplementation in general. On the contrary, balanced systems are powerful tools when used to prioritise stability—typically through proportional, finely divided dosing rather than intentionally large, singular doses. The key question is not whether a method is new or branded, but whether it minimises chemical stress and supports the long‑term physiological needs of corals.

For aquarists seeking optimal coral growth and long‑term stability, the priorities should be clear:

- First, keep alkalinity very stable and minimise daily swings; small, frequent additions that match consumption are preferable to large, infrequent ones.

- Second, maintain a consistently high, stable pH by managing CO₂ through good gas exchange, access to fresh air, and, where applicable, tools like refugia, light use of kalkwasser, or CO₂ scrubbers.

- Third, avoid significant, abrupt shifts in carbonate chemistry solely for the sake of a particular dosing time or aesthetic pH curve.

Any approach that increases the daily variability of alkalinity or pH—no matter how appealingly it is described—runs counter to well‑established principles of coral physiology and seawater chemistry. Stability in these core parameters remains the foundation of a healthy, resilient reef aquarium. Methods that prioritise timing tricks over chemical stability may appear attractive on paper. Still, the most reliable path to success remains disciplined consistency, sound chemistry, and respect for the biological limits of corals.

– Ali Akil, Modern Reef